Dinosaur feathers contain traces of ancient proteins, study finds

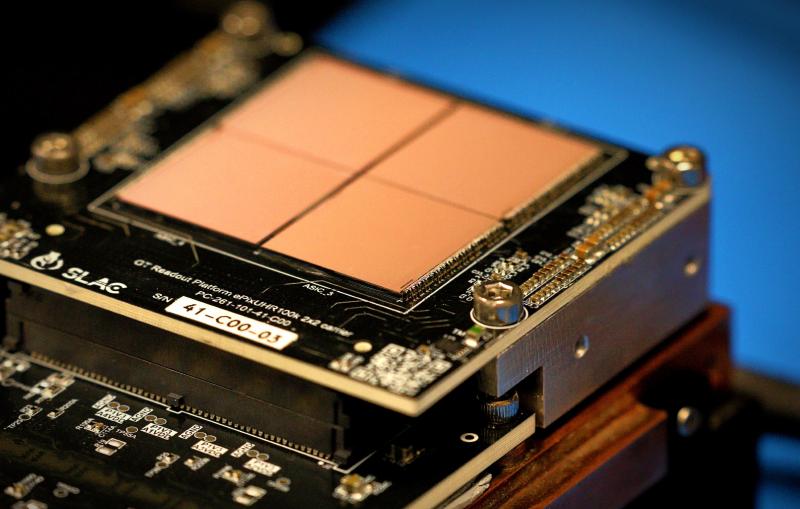

Powerful X-rays generated at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory help researchers shed new light on feather evolution.

By David Krause

How similar are dinosaurs to modern birds? This question is at the heart of a new study that examined how proteins found in dinosaur feathers changed over millions of years and under extreme heat.

Previous studies suggest that dinosaur feathers contained proteins that made them less stiff than modern bird feathers. Now, researchers with University College Cork (UCC), the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source (SSRL) at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and other institutions have discovered that dinosaur feathers originally had a very similar protein composition to those of modern birds. That result means that today’s bird feather chemistry likely originated much earlier than previously thought, perhaps as early as 125 million years ago.

“It’s really exciting to discover new similarities between dinosaurs and birds,” said Tiffany Slater, a paleontologist at UCC and lead author on the new study. “Using X-rays and infrared light, we found that feathers from the dinosaur Sinornithosaurus contained lots of beta-proteins, just like feathers of birds today. This finding validates our hypothesis that dinosaur birds had stiff feathers – like in modern birds.”

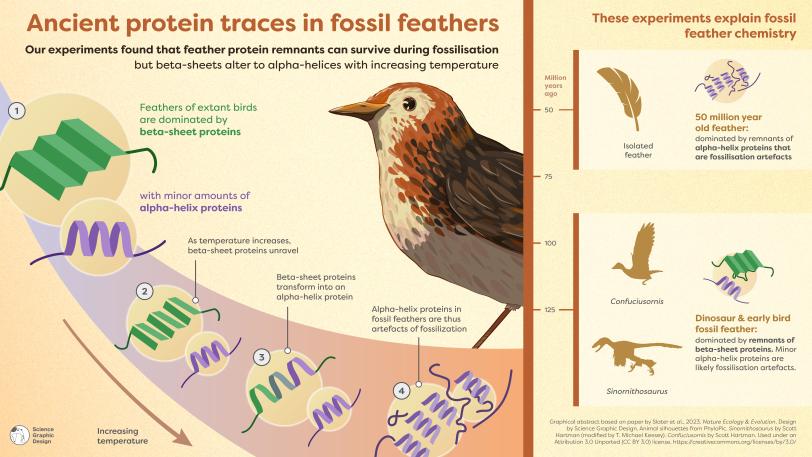

The crux of the issue is the protein mix. Earlier tests on dinosaur feathers found mostly alpha-keratin proteins, which result in less stiff feathers, whereas modern bird feathers are rich in beta-keratin proteins, which strengthen feathers for flight. Still, the researchers wondered whether that difference reflected the real chemistry of the feathers during life or an artifact of the fossilization process.

To find out, Slater and fellow UCC paleontologist Maria McNamara teamed with SSRL scientists to analyze 125-million-year-old feathers from the dinosaur Sinornithosaurus and the early bird Confuciusornis, plus a 50-million-year-old feather from the U.S. They published their results today in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

To detect the proteins in the ancient feathers, researchers placed the fossils in front of SSRL’s powerful X-rays, which revealed whether key components of beta-proteins were present. This helped the researchers determine if a sample’s beta-proteins were still in their “native” form or if they had altered over time – and how that alteration proceeds chemically, SSRL scientist Sam Webb said.

The team also performed separate experiments that simulate the temperatures that the fossils are subjected to over time, Webb said. These experiments showed that alpha-proteins can form in a fossil due to the fossilization process, rather than being part of the feather during life.

The analysis showed that while some fossil feathers contain lots of alpha-proteins, they were likely not there originally, but instead formed over time. They formed due to the high extreme heat that fossils experience.

“Our experiments help explain that this weird chemical discrepancy is the result of protein degradation during the fossilization process,” Slater said. “So although some dinosaur feathers do preserve traces of the original beta-proteins, other fossil feathers contain alpha-proteins that formed during fossilization.”

“The idea that original protein compositions may change over time is an often overlooked aspect of looking at biomarkers from deep time,” Webb said. “Comparing our X-ray spectroscopy results to the additional lab measurements of experimentally heated feather samples helped calibrate our findings.”

"Traces of ancient biomolecules can clearly survive for millions of years, but you can’t read the fossil record literally because even seemingly well-preserved fossil tissues have been cooked and squashed during fossilization," said Maria McNamara, senior author on the study.

“We’re developing new tools to understand what happens during fossilization and unlock the chemical secrets of fossils," McNamara said. "This will give us exciting new insights into evolution.”

This article is based on a press release from University College Cork.

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: Slater, McNamara, Webb et al., Nature Ecology and Evolution, 21 September 2023 (doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02177-8)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.